Japanese Mexican survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings

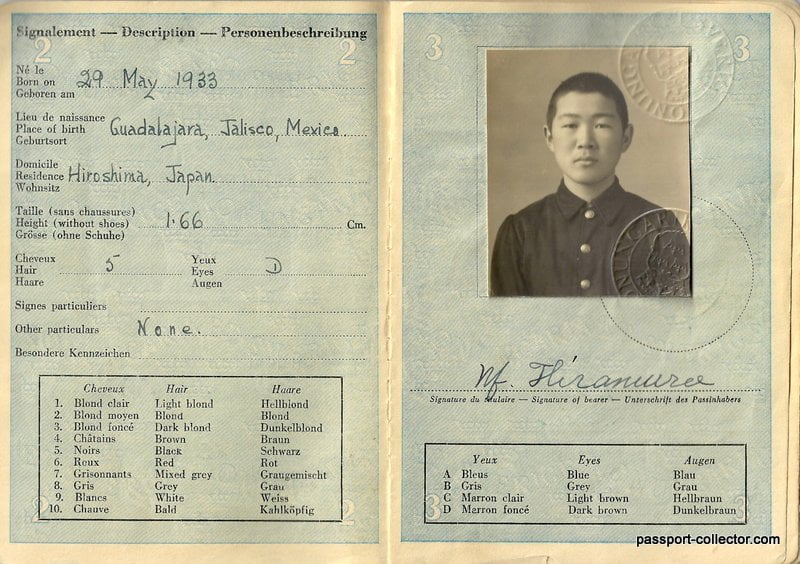

This August, Japan set to mark 75 years since Hiroshima, Nagasaki atomic bombing. Read the story of two Japanese-Mexican survivors and see the passport of Fernando Hiramuro issued by the Swedish embassy in Tokyo. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

The people of both cities paid for the end of the war with their own deaths and the destruction of their cities, but those who managed to survive to continue to suffer the effects of the radiation left by those terrible weapons. The war exacted enormous sacrifices from the Japanese people. Before the atomic bombs were dropped, the people of Japan had already suffered tremendously to maintain the war effort demanded by military leaders. Even though the elderly, women, and children did not participate in the battlefronts, they sustained the war effort with their work and sacrifice.

By early 1945, some of Japan’s largest cities had already been hit by U.S. bombs; Tokyo in particular was targeted by the most intense bombing of World War II, leaving more than 80,000 people dead. Homeless and lacking food, it was the people of Japan who were punished by the U.S. armed forces.

Moreover, starting in December 1941, the communities of Japanese immigrants in the United States, Canada, and Latin America, despite not being on the battlefield, were interned and persecuted. The children of immigrants—people who had been born in America but were in Japan when the war started—suffered twice due to losing all contact with their families and experiencing the suffering of the Japanese population. Some of them became hibakusha, which is, survivors of the atomic bombs.

Here are two of them: Fernando Hiramuro, who lived in Hiroshima, and Yasuaki Yamashita from Nagasaki. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

Toraichi Hiramuro, Fernando’s father, was one of the 100,000 emigrants who left the Hiroshima Prefecture for America in the first decades of the 20th century. In 1907, just 16 years old, Toraichi immigrated to Peru to work on one of the sugar plantations hiring large numbers of Japanese workers. However, rather than continue tolerating the terrible and exploitative conditions of plantation work, Hiramuro moved to Lima to work as a gardener. He saved up enough money for boat passage with the goal of entering Mexico and then crossing into the United States as a “bracero,” or guest worker.

In 1912, in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, Toraichi finally reached the port of Guaymas, Sonora, very close to the U.S. border. In this region, the U.S. railroad company Southern Pacific hired a large number of Chinese and Japanese workers to build the main rail lines that would unite the U.S. border with the city of Guadalajara in central Mexico. Toraichi joined the company as a gardener’s assistant in the small hospital built by Southern Pacific for its employees in the town of Empalme, Sonora. He later moved up through various positions until becoming a nurse’s assistant and decided to stay in Mexico permanently.

Towards the end of the 1920s, the rail company built a large hospital in Guadalajara and sent Toraichi to San Francisco, California for training in operating an X-ray machine. In early 1930, Toraichi used his savings to travel to Hiroshima in search of a partner with whom he could start a family. Unlike most of the emigrants who met and married fiancées, they knew only through letters, Toraichi traveled to his native country to meet and marry Kiyoko Hirotani. The Hiramuro’s first daughter, Clara Sumie, was born in Guadalajara in 1931. Fernando Minoru was born two years later and Concepción Michie was born in 1939.

The Hiramuros were financially well-off, as Toraichi had worked his way up to director of the X-ray department and earned a good salary in dollars. With their savings, the Hiramuros planned to return to Japan permanently and in the fall of 1940, the five members of the family traveled to Hiroshima, where Fernando began attending elementary school. Toraichi returned to his job in Guadalajara with the goal of joining his family, now installed in Hiroshima, at a later time. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

When the Pacific War began and Mexico and Japan broke off relations, all channels of communication between Toraichi and his family ended, and he was unable to send them financial assistance as well. Under these conditions, Kiyoko had to find a way to support her children. Fortunately, she owned a house she could rent out, enabling them to survive the war even though each year goods became increasingly scarce for the entire population.

As the opposing forces came closer to the Japanese archipelago, military commanders began to prepare the population for an imminent U.S. invasion. Fernando and his neighborhood friends went to school in small battalions of five individuals led by a sergeant.

In April 1945, the government authorities decided to send students from third to sixth grades to the countryside because of the danger of bombings in urban centers. Fernando and his friends moved to Tsuta, a farming town of rice fields and streams of crystalline water located 20 kilometers from Hiroshima. The school took refuge there in a Buddhist temple. Goods were very scarce and food rationing during those months became increasingly strict: Most of the children attended school without shoes or wore sandals made of rice straw.

On August 6, 1945, when the first atomic bomb was dropped, Fernando was lining up with his classmates during the traditional ceremony marking the start of the school day, where they listened to short speeches by the teachers and participated in the mandatory greeting to the Emperor. Before the ceremony had finished, the atomic bomb exploded, at 8:15 a.m. Fernando didn’t hear an unusual noise, but he saw a light as intense as thousands of simultaneous rays of lightning, blinding him for a moment; then in the distance, he saw a huge column of smoke and afterward felt the blast wave. Fortunately, the village of Tsuta was surrounded by hills, so the students didn’t grasp the magnitude of the disaster and destruction, even though the blast wave blew out all the windows of the temple. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

It wasn’t until the late afternoon that the first news arrived as people began returning to the town with burns and described the massive disaster, without knowing then that it had been caused by an atomic bomb that would result in even more death over many years to come.

The students were kept at the school, so Fernando didn’t find out until weeks later that his family had survived. His mother sent him a letter in which she wrote that she and little Concepción had been attending a neighborhood meeting when the explosion occurred, while Clara, who was working in a factory alongside her high school classmates, was unharmed. However, she had witnessed thousands of deaths and the destruction of the city. Clara and the other students, fearing another explosion, fled into a nearby forest and she didn’t return home until the next day. The family home, although still standing, was tilted and severely damaged. For several days the Hiramuro family and Fernando’s grandmother had to sleep in a plantation near the house because the damage made it unsafe to sleep inside.

At noon on August 15, the students gathered in the temple to listen to an important message from the Emperor on the radio. In his speech, Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender; however, the language he used was somewhat confusing for the students and many adults didn’t clearly understand what he meant to say. It wasn’t until the following day that government authorities came to the school to explain that Japan had surrendered. The students, who like the rest of the population believed that Japan would win the war, were hugely disappointed.

In the first days of September, before the war ended, Fernando’s school returned once again to its campus in Hiroshima. That was when Fernando finally saw how badly the city had been destroyed. The roof of the train station was gone and much of the station was charred. It was a rainy day and because there was no electricity, the city was shrouded in darkness.

Classes began at the old campus the day after the return to Hiroshima, although the students and teachers spent the week cleaning and repairing the damage caused by the bomb. Students found pieces of wood and shards of glass everywhere. All of the doors and windows had to be repaired, but since there was no glass to replace them, the students simply endured the freezing wind that penetrated every classroom. Classes were only held in the morning, so Fernando had time to repair his own house, which was full of leaks. The wall panels, which were made of an earthen mixture, had fallen, so the family reattached them to bamboo mesh. With help from neighbors and several hydraulic jacks, the house was straightened once again. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

For the Hiramuro family, the following years were as or more difficult than the war years. The lack of food became more severe and because the house Fernando’s mother owned in the city center had burned, they no longer received rental income from it.

Kiyoko brought a Singer sewing machine with her from Mexico, so she began sewing and repairing clothing, which most people needed because it was impossible to buy new clothes. Mrs. Hiramuro repaired hundreds of jackets and wool coats using the lining of the clothes, which was not as worn out. When customers didn’t have money to pay, they bartered various goods; Kiyoko received packs of cigarettes which she used to buy fresh vegetables and the rice sold by peasants on the outskirts of the city. The famine was so severe and life-threatening that the occupying authorities requested millions of tons of food assistance, which was distributed to the population to prevent riots.

In 1946, the Hiramuro family received two pieces of good news. A letter from Toraichi in Guadalajara finally arrived after communication resumed. He told them that authorization had been given for food and medical assistance, so essential for survival, and which immigrants to America had begun to send in large quantities to their family members. Also, Fernando completed elementary school and entered high school, which was a source of great pride for the family.

That year, thousands of emigrants who, like the Hiramuro children, had been born in and were citizens of a country in America, filed requests to return. These requests were finally granted in 1950. Returning wasn’t easy, since permission to leave could only be granted by the U.S. authorities. The Swedish embassy, which represented Mexico’s interests in Japan, granted the family passports so they could travel. Toraichi purchased tickets on a boat that brought them to San Francisco, California, where he was waiting for them. The family then traveled together in first-class train coaches to Guadalajara, thanks to Toraichi’s position as a Southern Pacific employee. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

The family’s reinsertion was difficult, despite their enormous happiness and relief at returning to Mexico. The Hiramuros had been separated for more than 10 years and the children had forgotten how to speak Spanish. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

Furthermore, Fernando’s schooling in Japan wasn’t recognized in Mexico, so he was forced to enter sixth grade. Despite these problems, Fernando wanted to continue studying, so he decided to repeat that year and then completed high school. After graduating, he enrolled at the University of Guadalajara where he studied medicine, specializing in orthopedics. He earned his orthopedic medicine degree with the highest honors and for more than 50 years taught many generations of doctors who graduated from that university.

He married Margarita Shoji, who was born in Mexico to Japanese parents. Fernando died in 2014; his sister Clara had died in 1957. Concepción still lives in Guadalajara.

Yasuaki Yamashita was born in 1939 in Nagasaki. Until the second atomic bomb exploded in the city where he was born on August 9, 1945, Yasuaki’s entire life had been one of war, since Japan had been immersed in its occupation of China since 1931, well before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The long period of sacrifice imposed by these conflicts is known by the Japanese as the “dark valley,” or kurai tanima.

Although Yasuaki grew up during the most difficult part of the war, he still had fun playing with his friends and trapping crickets and cicadas in the mountains near his home. The children were used to the wailing sirens that announced the arrival of the American bombers. The people knew they were supposed to enter the air raid shelters when the alert sounded, as had already happened several times before the atomic bomb was dropped. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

Yasuaki accompanied his mother to neighborhood meetings where residents organized themselves and received military training. The neighborhood organization, known as tonarigumi, played a key role in sustaining the war effort. Toward the end of the war, women began receiving training in the use of bamboo spears, to defend themselves against the U.S. army if it succeeded in occupying Japan.

Although the military commanders insisted in their propaganda that Japan could not be defeated, they simultaneously promoted the spirit of gyokusai among the people; that is, the idea that it was better to die honorably than capitulate or surrender to the enemy. Even after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, the Supreme Council made the decision to continue fighting the war to the end, defying Emperor Hirohito himself.

Yasuaki’s family was large: in addition to his father and mother, there were six siblings. The three oldest brothers had been recruited into the army, while the three sisters attended school. Yasuaki’s father worked for one of the largest and most important companies in Japan: Mitsubishi. This large conglomerate, or zaibatsu, manufactured weapons and airplanes and was in charge of the Nagasaki shipyards, so it was one of the bombing targets chosen by the U.S. army. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

On August 9, when the bomb was dropped at 11:02 in the morning, Yasuaki hadn’t gone out with his friends to look for insects. Along with his mother and one of his sisters, he listened to the siren and radio warning that an enemy plane was approaching, so they entered the house on their way to the shelter underneath. Before they reached the shelter, they felt an intense light that blinded them, and then a tremendous force threw them to the ground.

Yasuaki’s mother was able to protect him with her body; crawling through the darkness, they entered the shelter as countless objects flew around them. The house had been destroyed; only the columns supporting the roof and some walls remained. Yasuaki’s sister told her mother that some oil had fallen on her head, but it was actually blood from cuts caused by broken glass. After a few minutes, they began walking toward a shelter in the mountains, from where they could observe the few buildings that remained intact in the city and the fires all around.

Yasuaki’s father, sisters, and friends also arrived at the community shelter in the mountains. One of the girls had burns all over her back and died the next day. Under instructions from the authorities, Yasuaki’s father and hundreds of other volunteers went to the epicenter of the explosion to help the survivors, finding thousands of cadavers. Because he worked day and night in that area, Mr. Yamashita was exposed to intense radiation, which made him take ill suddenly. He died several months later. It has been estimated that more than 70,000 people were killed instantly by the explosion or died in the weeks afterward. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

In the weeks following the dropping of the bomb, the suffering of the people increased because of a lack of food, while the number of wounded and dead rose each day. To find something to eat, Yasuaki’s mother decided to take the children to stay with relatives who lived outside the city. To get there, they had to walk through the area where the bomb had fallen, where they saw thousands of charred bodies that couldn’t be removed.

After a few days, Yasuaki and his mother and sisters returned to Nagasaki, unable to find enough provisions. Using the burned walls and materials they were able to recover from the ruins, they rebuilt and covered the largest holes in the house so at least they wouldn’t have to sleep outdoors.

In the following months, the situation of the population changed radically in the face of almost total destruction of the cities and the country’s economy, as well as the occupation by U.S. forces. Yasuaki entered primary school. Most of the children attended school without shoes and wearing mended clothing because of the total lack of such goods, which could only be obtained in the black market for exorbitant prices. The textbooks distributed in the schools were the same ones used during the war, but the children crossed out the paragraphs praising the Emperor and Japan’s era of militarism.

The worst aspect of those years continued to be the scarcity of food, which resulted in famine. The U.S. army had to distribute provisions in the schools. Yasuaki remembers vividly the day he drank powdered milk and ate raisins and some crackers that seemed to him like manna from heaven. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

Encounters between the soldiers and the population during the U.S. occupation were unexpected and surprising for both sides. The U.S. soldiers weren’t the “demons” with horns that Yasuaki and his friends had imagined, based on the information the Japanese military disseminated during the war. Nor was the Japanese population a horde of barbarians and fanatics, as the U.S. government had sustained. Both the Japanese and U.S. war propaganda had reached such an extreme as to propose that only extermination of the enemy would end the war. The U.S. troops found, on the contrary, a population ready to help while the Japanese population encountered a U.S. army that was disciplined, educated, and orderly—even friendly—such that the soldiers didn’t fire a single bullet during the seven years of occupation.

The struggle faced by the Japanese after the war was centered around the reconstruction of the country, which was in ruins. Yasuaki’s sister began working to earn some money and Yasuaki himself delivered newspapers to help support the family after his father died.

When Yasuaki was about to finish high school, he was stricken with a strange illness that manifested in hemorrhaging that appeared suddenly and caused him to faint as a result of sudden anemia. The medical tests he underwent showed no apparent explanation for these problems and to this day, a cause for them has never been determined. Because of the fainting, Yasuaki was unable to find a permanent job, since he frequently ended up in the hospital. It wasn’t until 1960 that he began working at the Japanese Red Cross Hospital for atomic bomb survivors, Nagasaki Genbaku Byoin, as a department administrator. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

In the hospital, Yasuaki became fully aware of the extent of the effects of the atomic bomb in causing a variety of diseases among the hibakusha, or survivors. Yasuaki’s work was not only administrative; he began to develop a very intense relationship with the patients, through direct contact with babies who were born with deformations and numerous patients with cancer caused by radiation exposure. In particular, he was greatly impressed by a young man his age who was diagnosed with leukemia and to whom Yasuaki donated blood every time he needed it. The physical deterioration and subsequent death of this young man greatly marked Yasuaki, such that every time he looked in the mirror, he was reminded that he could himself become ill at any time.

But Yasuaki was also the victim of discrimination caused by unfounded fear from one part of the population that believed they could be “infected by” the diseases of people exposed to radiation. Young women, in particular, faced rejection and found it difficult to find a husband because of the possibility that their children would be born with birth defects. From that time, Yasuaki hid the fact that he had survived the bombing and refused to talk about his experience, beginning a long period of silence on that chapter of his life. Japanese writer Kenzaburo Oe, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1994, has explained this behavior, pointing out that only survivors are entitled to remain silent if they wish to, as they attempt to forget that terrible experience. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

During this stage of his life, young Yasuaki developed an interest in Mexico. What was it about that country that caught his attention?

First, it was the music: A trio known as Los Panchos who sang boleros became very popular in Japan and even recorded their songs in Japanese. In addition, learning about Mexican culture, mural painting, and the history of the Meso-American peoples began to arouse interest among the Japanese people. A book by painter Tamiji Kitagawa, who lived in Mexico before the war, represented for Yasuaki another important incentive to study the history of that country and he also began studying Spanish with great enthusiasm and dedication.

Although he had a good job at the hospital, the pain of the patients and his desire to move away from that environment so full of suffering and discrimination motivated Yasuaki to seek, almost obsessively, a way to travel to Mexico. The occasion presented itself in 1968 during the Olympic Games in Mexico: the Japanese delegation needed a young person to work as an interpreter, and Yasuaki was quickly chosen.

When the Olympics were over, he decided to stay in Mexico and look for a job, which would enable him not only to deepen his knowledge of the Spanish language but also of pre-Hispanic peoples and their culture. He took several courses at the National Museum of Anthropology and began traveling to all of the archaeological zones in the country. His profound interest in Mexican culture led him to study the Náhautl language, so he could directly communicate with indigenous people. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

As a result of the expansion and rapid growth of the Japanese economy during these decades, hundreds of Japanese companies installed plants and offices in Mexico. With his command of the Spanish language, in early 1970 Yasuaki began working with company executives as an interpreter and translator. Because the work was intense and well-paid, in addition to his interest in the culture and people of Mexico, Yasuaki decided to stay in that country and even applied for Mexican citizenship.

Moreover, Yasuaki believed that the Mexican and Japanese cultures were not as different as they seemed to be, with Shintoist philosophy sharing many common aspects with the philosophy of the Meso-American peoples.

It wasn’t until 1995 that Yasuaki decided to break his silence as a hibakusha. In the city of Querétaro, a group of young people invited him to give a talk on his experience as a survivor of the atomic bomb, since they knew he had been born in Nagasaki. Initially, Yasuaki flatly refused, but he eventually agreed to give a talk. The lectures and conferences that he began to participate in starting at that time became for Yasuaki a kind of balm or therapy that enabled him to mitigate the enormous pain he had previously kept to himself.

Yasuaki also decided to contribute his personal effort to the global movement against the use of nuclear weapons and in favor of peace. This led him to join organized groups of survivors of the atomic bomb in the United States as well as organizations that promote nuclear disarmament in several countries.

Yasuaki has been an untiring crusader who travels to numerous countries around the world to share, in clear detail, his experience in Nagasaki. He has presented numerous times in organizations such as the United Nations and for various governments, explaining his reasons for opposing the complete destruction of the nuclear arsenal. The work that Yasuaki carries out with young people is something he is particularly passionate about. He visits many schools to ensure that the students will share his words and continue his fight against atomic weapons. The disaster at the nuclear terminal at Fukushima in 2011 in Japan, after the earthquake and tsunami, demonstrated that even peaceful use of atomic energy for power plants could result at the end of humanity. Survivors Hiroshima Nagasaki bombings

At 77 years of age, Yasuaki is passionate about two activities: His work on behalf of the peace movement, as his Japanese name, signifies (保昭), to ensure that no one else has to suffer the consequences of an atomic tragedy like the one experienced by the people of Nagasaki and Hiroshima. With the same intensity, his paintings and pottery have led to recognition and awards as an artist. He currently lives in San Miguel Allende, Guanajuato.

Kenzaburo Oe’s definition of the character of the hibakusha is accurate; he says that when they decide to speak, they do so with all of their energy. None of us, notes the Japanese writer, should remain passive or merely moved by their stories; rather, we should “accompany them because it is the only way we can continue being true human beings.”

Nagasaki – why did the US drop the second bomb? | DW Documentary

This story was first published in 2016 – http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2016/7/7/japoneses-mexicanos-sobrevivientes-1/

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...