My German Third Reich passport found in Shanghai

My German Third Reich passport found in Shanghai

(by PETER NASH, Sydney)

Sitting at the computer, my wife Rieke knew something special had come into the ‘inbox’ and called me immediately. The unknown sender titled the Subject: “Lost Passport in Shanghai” – a topic I was familiar with as I had initiated connections to owners of two German Passports a few years earlier.

However, there was an attachment labeled Ingeborg Nachemstein – my mother’s exact name. This was a scan of a section inside a passport, showing the name (Ingeborg Sara Nachemstein), date and place of birth, some other personal details, and a photo. But it also revealed that the passport holder had a child listing date of birth and name: Peter – ME!

I was amazed, if not completely surprised. Three years ago, the Rickshaw website had an article seeking the owners of two German passports that turned up at a Shanghai ‘flea market’. Ever since, I thought – “so how many others are there to be found?” My German Third Reich passport found in Shanghai

The message’s sender was Thomas Dorn, a German citizen living and working in Shanghai already for six years, having worked in various parts of Asia for many years. In his leisure time, Thomas’s hobby is roaming around Shanghai, looking for historical posters and other curiosities about China’s evolution in recent decades. On that particular weekend, he had ended up at a shop cum museum of Chinese propaganda posters. A fluent Chinese speaker, Thomas conversed with the museum owner/collector.

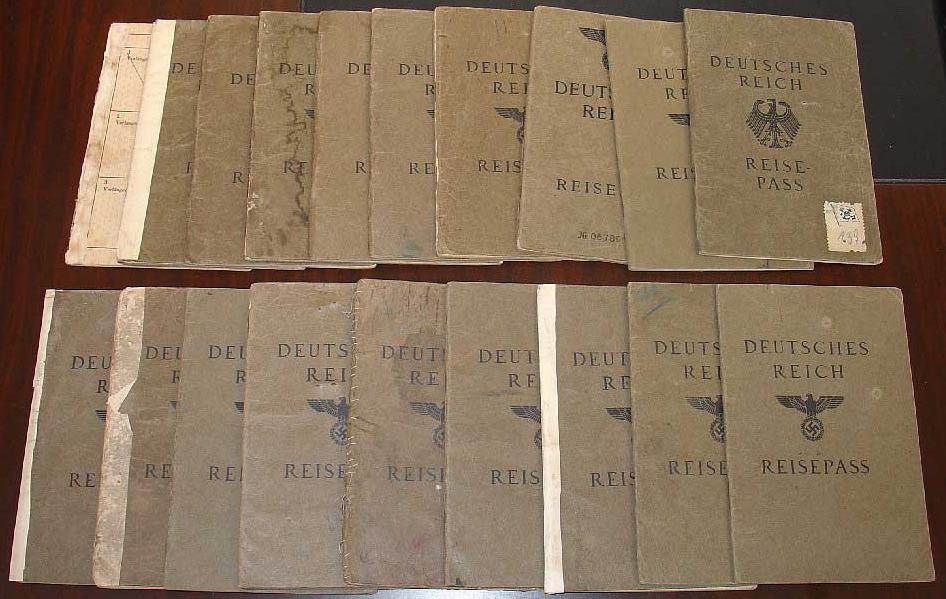

After a short while of getting to know each other better and realizing Thomas’ origins, the owner, Mr. Yang Pei Ming, produced a box containing 19 German passports. From the Eagle and Swastika (Hakenkreuz) on the cover and the “J” inside, Thomas immediately knew their significance and, having lived in Shanghai for several years, was also aware of the story of the thousands of German, Austrian, and other European Jews who fled the Nazi era and found a haven in Shanghai. As he slowly turned the pages of several passports, his “hair stood on end,” realizing the pain, blood, and tears that these passport holders had endured through their long journey to Shanghai, the displacement and loss of family, as well as hardships of refugee life. My German Third Reich passport was found in Shanghai.

Instinctively drawn to the need to find the owners or a descendant, Thomas was galvanized into action. Gathering his thoughts, he used his mobile phone to take photos of those passports listing children, hoping some might still be alive and that he could trace them. The first Passport he photographed and subsequently searched on was that of my mother and me. On returning to his computer, he ‘Googled’ my name – my birth name – and, within 0.16 seconds, found more than ten ‘hits’ for me, resulting from my previous publications and lectures on the Jews of Shanghai. Not only did the first link he opened list my adopted name and my birth name, but it also gave an email address.

Within 60 seconds of receiving Thomas’ email, I called him in Shanghai, taking advantage of the relatively small time difference. It was my turn to startle him! Not expecting such a quick response, he thought it was his boss calling from Germany. Although his English is fluent, we mainly spoke in German, which I am also still articulate. I was naturally curious about how Mr. Yang came into possession of such a large number of passports. According to Mr. Yang, there are around 100 passports of German-Jewish refugees to China circulating at the moment – another known lot of 5 passports, plus Mr. Yang’s 19, mean there may be another 75 still waiting to be discovered.

We received an eviction notice from the owners of our apartment block, dated November 25, 1938, that is, two weeks after Kristallnacht, quoting a recently enacted law required that Jews could no longer live under the same roof as Aryans and that we had to vacate our apartment in Charlottenburg, Berlin, by no later than December 31, 1938. As entry to countries such as the United States, Australia, and elsewhere was severely restricted or unaffordable, this forced us to take the only viable option, the “open port” of Shanghai – also coined “Port of Last Resort.” Tickets for sailing on the Norddeutscher Lloyd’s “SS Scharnhorst” were purchased in Berlin helped by an ‘under-the-table’ sum to the shipping clerk. Boarding was in Genoa, Italy. With my parents, my mother’s parents, and her brother, we finally left Berlin in April 1939.

The rubber stamps can track the route and dates in the Passport:

- April 24 through the Brenner Pass, Austria, into Italy, April 24 is also verified by a Train Ticket from München to Ventimiglia

- On April 26, we sailed from Genoa and headed to the Suez Canal (Enjoying First Class amenities aboard the SS Scharnhorst)

- May 7, we arrived at Colombo

- On May 17, we arrived in Hongkong

And finally, two days later, on May 19, sailing along the Whangpoo River, we arrived in Shanghai. Before leaving Berlin, my grandfather Isidor Lewin was devastated to leave his beloved Germany and suffered a heart attack. He died soon after our arrival on June 19, 1939, and was buried in the Baikal Road Cemetery, one of the first refugees buried in Shanghai. The 24-day voyage from Genoa to Shanghai was a welcome relief and nourishing holiday for my family after the previous traumatic months and years under Nazi German rule. But it was immediately erased by the harsh realities of the appalling conditions and tough life nearly all the other refugees had to endure directly after arrival.

How these passports came to be left behind in Shanghai has so far not been uncovered. The Nazi-issued passports did not serve any other purpose when World War 2 ended, but many refugees returned with their original passports. Indeed I have in my possession the Passport of my mother’s sister and her husband, and I know the one belonging to my uncle’s wife exists. One theory is that the passports may have been collected from certain groups of stateless refugees during their post-war emigration and replaced by other qualifying identity documents for entry to the country of migration.

There is no definitive answer as to how these documents have survived and under what circumstances they recently surfaced. In the late 1950s, not long before the start of the Cultural Revolution under Chairman Mao, there was mass ‘dumping’ of records and paraphernalia relating to Shanghai’s Western population. Peddlers, sorting through the rubbish for recyclables and items of value, apparently picked out these documents and sold them to curio-stall owners rather than as waste paper to be pulped. Thus, the passports may have spent many years in a dusty corner in some of Shanghai’s flea market stalls.

Other items have surfaced similarly. An example is the recently found Jewish tombstones, some complete, some partial, so far numbering over 80 – including that of the father of our well-known Rickshaw website contributor, Ralph Harpuder (see his article). It is known that the tombstones of the four Jewish cemeteries in Shanghai, numbering about 3500, were pulled up and re-interred outside of Shanghai in 1958. Later they were again pulled out, many broken up or used as paving stones or for other building works. My German Third Reich passport was found in Shanghai.

What the Chinese holders will do with these passports is uncertain. Some have been sold. In fact, in 2001, while leading a tour of German medical students, Prof. Paul Unschuld came across a stallholder outside of Shanghai who possessed two passports. He bought them and later proceeded to find the owners and their families.

Both Thomas and I agreed that money should not change hands for the return of my mother’s Passport. We explored the possibilities of having it returned, and I decided to contact Mr. Yang directly. His response gave me hope that I may get it from him. Thomas has since visited Sydney and brought our Passport with him. He handed the Passport over to me – ‘on loan’ from Mr. Yang at the Sydney Jewish Museum. This again gave me the feeling of trust that Mr. Yang would do the ‘right thing’ and return our Passport. A planned Reunion of ex-Shanghailanders in June 2008 in Shanghai may be the proper forum to hand over some of the passports to their owners and surviving family members of the Shanghai Jewish refugee museum. This is an extraordinary instance in a chapter of Holocaust survivor history with a good ending.

Peter Nash has spent more than 20 years actively researching his family history and has helped many searches for a family who also found a haven in Shanghai. He has lectured and authored articles on the Jews of China. He is a volunteer guide at the Holocaust-orientated Sydney Jewish Museum. My German Third Reich passport was found in Shanghai.

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...