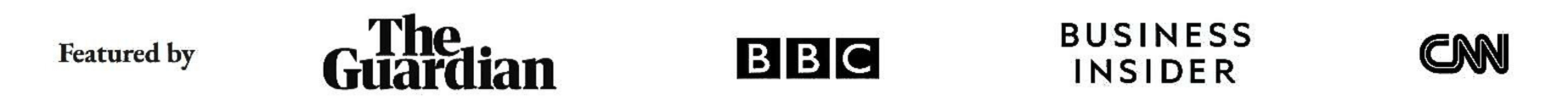

Passport Carl Szokoll – Stauffenberg – Valkyrie – 20 July Plot 1944

Passport Carl Szokoll – Stauffenberg – Valkyrie – July 20 Plot 1944, von Stauffenberg’s linkman in Vienna during the plot to assassinate Hitler.

Szokoll was an Austrian infantry regiment officer, absorbed like the rest of the national army into the Wehrmacht after the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. His colonel issued the order to implement Valkyrie in Vienna. Szokoll was one of the last persons talking with Stauffenberg on the phone before his arrest, and he was one of the very few survivors of the officers involved in the “Radetzky Operation.”

Szokoll was an Austrian infantry regiment officer, absorbed like the rest of the national army into the Wehrmacht after the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938. His colonel issued the order to implement Valkyrie in Vienna. Szokoll was one of the last persons talking with Stauffenberg on the phone before his arrest, and he was one of the very few survivors of the officers involved in the “Radetzky Operation.”

The Passport

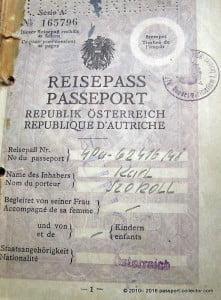

is a series “A,” Republic of Austria type. The cover page is missing, and so is the passport picture. However, his passport was issued in Vienna on June 18, 1948. It might have been his very first passport after the end of WWII. His travel document has 48 pages, and ALL pages are filled with stamps and visas.

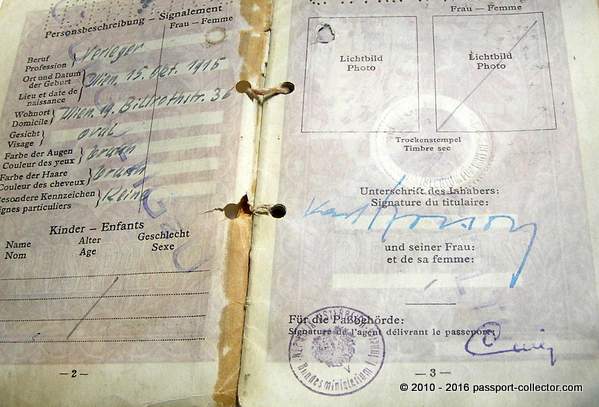

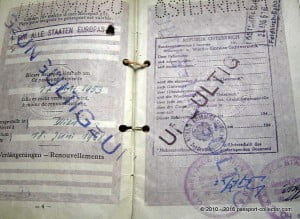

The several visas issued by the Allied High Commission Travel Board are very interesting. Six such visas total and four different AMG stamps Gratis, $4, 8DM, and 16DM. This is awesome, as I have never seen this variation of AMG stamps in ONE passport. Take a look also at the EXIT visas to leave Austria. They also are unusual.

Further visas are from Switzerland, including revenue stamps, the UK, Switzerland, Germany, France, Spain, and several Yugoslavia. Very interesting is the big stamp (visa) from the Allied Forces stating “…is permitted to enter Berlin”, four languages (EN, FR, RU, GER), issued January 8, 1953. Never saw this kind of stamp/visa!

This is the second passport in my archive of a resistance fighter and member of the July 20 plot, and I am proud to have it!

Szokoll, then a captain, proceeded with a will to execute the plan, rounding up Nazi officials until the report that Hitler had survived and the coup had failed. His commander was sent to a concentration camp in the savage post-coup round-up. Szokoll’s disingenuous plea that he had only obeyed orders was accepted, and he escaped punishment, even though he was one of the last to talk to Stauffenberg on the telephone before the count’s arrest. He had placed his call to an untapped extension in a supply office at headquarters, a precautionary number given to Szokoll when they met early in 1944. Less than two weeks after the coup failed, Szokoll was promoted to his final rank of major.

Szokoll was born in Vienna, the son of a corporal in the Austro-Hungarian imperial army, also called Carl. He spent a period as a prisoner of war in Siberia and stayed in the service after the first world war. Carl junior therefore grew up in Viennese barracks. His father wanted him to do better than himself and sent the boy to a grammar school, where he excelled in class and on the sports field before enlisting in his father’s regiment in 1934 as an officer cadet. Two years later, he met his future wife, Christl Kukula, daughter of an industrialist and his Jewish wife.

After the Anschluss, Carl senior urged his son to give up the friendship, which threatened to ruin his army career under the Nazis. His punishment was mild: his transfer to a panzer unit was reversed, and he was sent back to the infantry. He fought in Poland and France before a wound put him behind a desk in Vienna. His father’s advice caused a longstanding rift. But the romance survived, and the couple married in 1946.

By then, Szokoll had earned the informal title of “Savior of Vienna.” After escaping the fate of many fellow conspirators and the penalty for his relationship with a “half-Jewish” girl, he took his life in his hands by putting out feelers from army headquarters to the Soviet military commanders as they closed in on Vienna.

His objective was to get them to treat Vienna as an open city, to prevent it from being destroyed as Berlin was in 1945. The Wehrmacht commander of the city, a general of Austrian origin, helped by withdrawing his troops.

But diehard Nazis discovered the plan, and three of Szokoll’s associates were executed while a reward was put on his head. Once again, he eluded punishment. On reaching the Russian lines, he was suspected of being an American spy but could convince his captors otherwise. He even went on to organize resistance to SS units planning to carry out Hitler’s order to fight the last man. Szokoll emerged unscathed. So, in the main, did his city.

He conducted talks with the Soviet city commandant and briefly acted as unofficial mayor. But the Russians again became suspicious of Szokoll, accusing him of spying for Germany. As usual, he had now talked his way out of trouble.

His hopes of a prominent role in the postwar regeneration of Austria, or at least Vienna, were dashed by returning professional political exiles, who took all the leading positions. His contribution to the resistance was honored with several awards, including the freedom of Vienna.

He turned to the cinema, making films that won international acclaim. A favorite theme was the need to awaken the conscience of the kind of the silent majority that allowed Hitler to come to power. Among his work is the script for the film Der Bockerer, the production of Die Letzte Brucke (the film that made Maria Schell famous), and his autobiography that became a bestseller and was working on a science-fiction novel with a peace theme when he died. His wife and their son survive him.

Carl Szokoll, officer and film-maker, born October 15, 1915; died August 25, 2004

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...