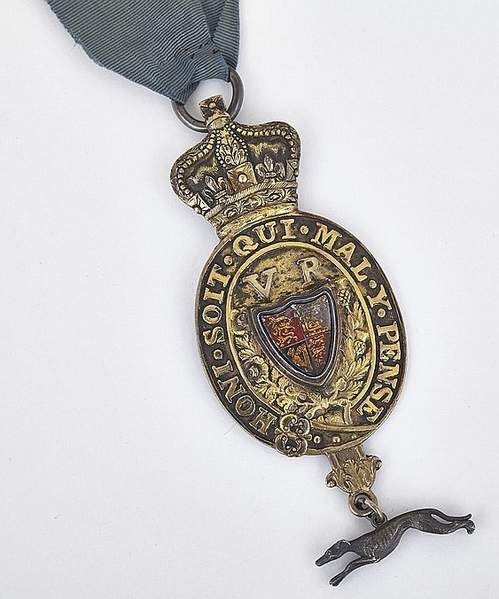

Queen’s Messenger Silver-Gilt Badge & Appointment

1845 named to William Chalmers with London marks and over struck maker’s mark I.N, the central poly chromed royal shield under VR within crowned motto garter with suspended silver greyhound, on blue grosgrain ribbon, together with original original appointment on laid paper issued by the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, signed and sealed February 8, 1845, metal height 5.75″ — 14.6 cm.Note:William Chalmers is named in The British or Imperial Almanac for the Year 1846 on page 106 under ‘Her Majesty’s Household – Office of Robes’ as one of the ‘Queen’s Own Messengers’.

History

Diplomatic relations between nations have always necessitated the relaying of sensitive messages. The King’s Messengers have been employed to carry Royal messages since the 15th century. Richard III reputedly employed a messenger to hand deliver his private papers in 1485.

Charles II employed four messengers. When asked how they were to be identified as His Majesty’s messengers, Charles II broke off four greyhounds from a silver breakfast platter and presented each with this token. This has remained the symbol of the Messenger to this day.

Originally each government department would have had their own messengers. These messengers were gentleman of high standing, and were unlikely to merely deliver packages. It is more likely they employed others to do their work for them.

In 1641 ‘Forty messengers of the Great Chamber of Ordinary’ were lodged in the Royal Palaces, under the orders of the Lord Chamberlain.

The formation of the Foreign Office in 1782 saw the King’s messengers take a more prominent role. The Messenger Service was now divided into two separate divisions, King’s Home Service Messengers and Corps of King’s Foreign Service.

Europe at War

The messenger role was particularly hazardous from 1795. With France at war with most of Europe including England, the Messenger’s role became not only important but also dangerous. A Messenger travelling through France was highly vulnerable.

It was now impossible to predict when a messenger would arrive back in London. These delays caused the Foreign Office to use Home Service Messengers for foreign duty. A restructure, in 1795, resulted in 30 messengers interchanged between Home and Foreign Service.

Unwanted servants, valets, sons of trusted servants and other ‘less desirables’ were now appointed, resulting in the Diplomatic Corps regarding them as ‘a very subordinate class’.

Some were killed whilst on duty. However, despite the dangers, the messengers still succeeded in their duties. One reported/notable story involved a messenger, thought to be Andrew Basilico:

Andrew Basilico was sent to Europe to deliver a package. This involved travelling through France. With the threat of the messenger being caught, the dispatch was written in a small corner of a sheet of paper. Basilico was caught and the French, on opening the packages, only found bundles of plain paper. Basilico, knowing indeed he was about to be caught, had eaten the corner of the dispatch. He was later exchanged for a French General.

Another interesting tale concerns a messenger who was to escort a prisoner back to London. He ended up taking the prisoner home. His wife dutifully cooked a meal for the three of them. With no guards, the husband and wife were obviously taking a considerable risk, and slept with a loaded pistol – not the sort of work you would volunteer to take home today! The prisoner is likely to have been a Gentleman or Officer rather than your usual rogue.

As well as heroics there were also disciplinary matters.

In 1834 a complaint was made against William Cookes returning from Vienna. The complaint from an Austrian Post Master at Dobra reported Cookes use of two carriages; the second being for a Mr Knight, gentleman. He commented: ‘what business has a messenger with two carriages?’ followed by ‘the idea of a man being his own avant courier has at least the merit of originality’.

Finances

The amount a Messenger could claim for each journey was predetermined with tables showing the amounts for every journey. Messengers often tried to make extra money by selling the empty seat in their carriage. This legitimately helped cover costs and provided a companion for the journey. But they charged heavily for the seat and in 1837 Lord Palmerston tried to prohibit this custom. This ban was however suspended after a series of memorandums from Lewis Hertslet to remove this ‘hardship’.

Lewis Hertslet was the Superintendent of Messengers, and Foreign Office Librarian until he retired in 1854. Appointed in 1824 he was under the direct authority of the Foreign Office.

Although there are no dedicated files on the service records of these messengers, you can trace their journeys and careers through various sources at The National Archives:

• The Foreign Office List includes the messengers by name

• Lewis Hertslet’s papers in FO 366, and the miscellaneous series in FO 95, contain financial papers relating to the messengers. These include the Oaths sworn by messengers, allowances for journeys and applications for pensions and sick leave.

One can also find lists of the dates of appointment, deaths and pensions received, the number of year’s service, and names of those who died in service. For example, Andrew Basilica was appointed on 5 October 1782 and retired after 31 years service on the 7 December 1813 with a pension of £266 13s 4d. He died on the 28 August 1824 leaving his wife a pension of £75.

There are plenty of records relating to the accounts, expenses and appointments of the messengers. These bills list the expenses claimed for each journey, and using these records you can trace an individual messenger’s career.

In 1824 Lewis Hertslet was promoted to Superintendent of Messengers. His changes to the Messenger service would last until the 20th century.

Today

The Corps of Queen’s Messengers still exists today, as not everything can be sent by electronic or registered mail. In 2005 there were reportedly 15 messengers in Her Majesty’s Service. They are still issued with a red passport. They still carry the official sealed diplomatic bag which cannot be inspected by customs officers.

Further reading

The papers of Lewis Hertslet are in The National Archives’ series FO 366, other records include FO 351; when he was the Foreign Office Librarian; and FO 95 Miscellaneous files.

The History of the King’s Messengers, V Wheeler-Holohan (Grayson and Grayson, 1935)

Source: https://history.blog.gov.uk/2014/03/25/the-silver-greyhound-the-messenger-service/

QUEEN’S MESSENGER SILVER-GILT BADGE & APPOINTMENT

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...