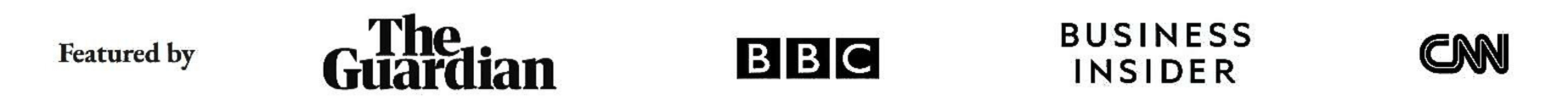

A remarkable Czechoslovak diplomatic passport and its bearer´s destiny

Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Written by fellow collector Z.Š. (Slovak Numismatic Society at Slovak Academy of Sciences) who is truly an expert when it comes to Czechoslovak passports and Id’s. However, his main interests are Numismatics.

The forming of Czechoslovak diplomatic service started already before the proclamation of its independence on 28 October 1918. The Czechoslovak National Council created on 13 June 1918 in Prague was recognized already on 29 June, 8 August, 3 and 9 September and on 3 October by France, Great Britain, USA, Japan, and Italy, while the Provisional Czechoslovak Government formed on 14 October in Paris was recognized on 16, 23 and 24 October 1918 by France, Great Britain, and Italy, respectively. Without any earlier experience in diplomacy, its members were confronted with the necessity to establish contacts with other states and lead negotiations with their representatives to anchor the international position of emerging Czechoslovakia. The first legacy was established on 26 October in Paris, two days before the independence declaration. The next two followed on 28 and 29 October in Vienna and Budapest. The absence of specialized diplomatic personnel was solved by engaging lawyers, teachers, higher officials of various administrative bodies, and demobilized Czechoslovak legionaries. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

It was also the destiny of JUDr. František Havlíček. He was born on 5 April 1886 in Kiev in Russian Empire. In 1911 he graduated from the Faculty of Law of the Bohemian University in Prague, continued studies in Vienna, and practiced at the Land Court in Prague. In 1916 he started to work in the Justice Department of the War Ministry in Vienna. Already on the day of the independence declaration, he entered in service of the newly established Office of the Czechoslovak Plenipotentiary in Vienna, as a personal secretary of the plenipotentiary Vlastimil Tusar (a Moravian social democrat, since 1911 deputy of the Austrian Parliament in Vienna, since late 1917 active supporter the Czechoslovak independence movement). In January 1920, after Tusar´s mission in Vienna, Havlíček followed him to Prague. Under both Tusar´s governments in 1919-1920, he worked in the Ministerial Council’s Presidium. After Tusar´s demission in September 1920, he followed him to diplomacy. Since November 1920, he accompanied him as the legation Counselor at the embassy in Berlin. After Tusar´s death on 22 March 1924, he led this embassy as chargé d´affaires until 28 March 1925. Then he worked for two years in the Central and East European Department of the Political Section of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague. From 21 October 1927 until 31 October 1931, he became ambassador to Belgium. On 1 May 1932, after a short stage at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he was appointed ambassador to Japan, where he fulfilled his mission until 16 March 1939. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Two days earlier, on 14 March 1939, under Hitler´s pressure, Slovakia declared independence. The next day morning, Nazi Germany occupied the rest of two western parts of Czechoslovakia. Thus Czechoslovakia ceased to exist de facto. After complex two-week negotiations, Slovakia was transformed into a formally independent state, under Germany´s protection. Bohemia and Moravia’s rests were incorporated into the Reich as a Protectorate, with limited internal autonomy, but without international suzerainty. Germany overtook the administration of foreign affairs of the rests of Bohemia and Moravia. Consequently, on 16 March, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague was dissolved. At 18.30, all 74 Czechoslovak ambassadors got the telegram from the (at that moment already former) Czechoslovak minister of foreign affairs Dr. František Chvalkovský to give over their offices, buildings, and all documents to representatives of German diplomacy in the respective states. However, 18 ambassadors did not fulfill that order. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Individual states reacted to the new situation differently. Some of them allowed the Czechoslovak diplomats, who declared their disaccord with the German occupation and rejected to give over their offices to German diplomats, to continue their activity as representatives of Czechoslovakia. In France and Great Britain and their colonies, to a certain degree in Poland, they could even start to prepare conditions for organizing resistance in exile. On the contrary, the allies or satellites of Nazi Germany immediately stopped to recognize Czechoslovakia and forced the Czechoslovak diplomats to liquidate their legations. Somewhat curious was the attitude of the Soviet Union. Until closing the pact Ribbentrop-Molotov, the Czechoslovak embassy continued its activity, as the Soviet Union protested against Czechoslovakia’s German occupation in March 1939. But in August 1939, the Soviet Commissariat of Foreign Affairs asked the ambassador Dr. Zdeněk Fierlinger to leave the Soviet Union. However, shortly after the German attack of 22 June 1941, the diplomatic relations were restored, a collaboration treaty was signed, and Dr. Fierlinger returned to Moscow on 20 August 1941.

Japan, as a German ally, stopped recognizing Czechoslovakia on 16 March 1939 and broke diplomatic relations. The ambassador Havlíček had to liquidate the embassy and four consulates in Japan. He executed that task, but with a carefully arranged delay, during which he succeeded in saving some Czechoslovak ownership against the German confiscation. Then he remained in Japan. As he disagreed with the German occupation, he entered in early 1940 in contact with Czechoslovak resistance centers in France and England, offering them information services. Some sources even mention him at that time as a Czechoslovak intelligence officer. Besides it, he attempted to act in Japan as a private unofficial representative of Czechoslovakia. However, the Japanese government accused him of espionage and arrested him in spring 1941 for one year. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

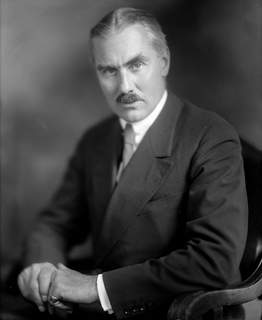

Activities of the USA diplomacy determined his next destiny. Even though the US ambassador to Japan, Joseph Clark Grew (27 May 1880 – 25 August 1965) (Fig. 1) declared, in the name of USA, the war to Japan on 8 December 1941, after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and he himself was interned for some time, the Americans negotiated with Japan and other states of Axis about mutual repatriation of their diplomat and citizens of other western allies. Thanks to it, F. Havlíček was let free, and on 25 June 1942, he was allowed to leave Japan together with other 1450 repatriates, citizens of the USA and other Allied countries. They traveled on the Japan liner Asama Maru overtaken by the Japan Imperial Navy, accompanied by the Italian steamer Conte Verde to the neutral port Lourenço Marques in Mozambique, the then colony of Portugal. Reciprocally, 1062 Japanese diplomats with the ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura left the USA with the liner Gripsholm, originally registered in Sweden, chartered by the USA, but operating under the flag of the International Red Cross. After arriving of all liners at Lourenço Marques, the control and exchange of repatriates were carried out on 22 July 1942. On 27 July, the Allies diplomats continued traveling with Gripsholm via Rio de Janeiro to New Jersey. From there, Havliček traveled to Great Britain. He arrived in Liverpool on 9 October 1942. The British civil authorities registered his stay in England on 12 October. In England, he entered the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the meanwhile recognized Czechoslovak exile government in London. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

After the war, he continued to work at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague, maintaining the title Ambassador. He also became president of the Commission for Investigation of War Criminals, as well as Councillor for revision of service instructions. After the “Victorious February” of 1948, when the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia became the country’s absolute ruler, profound personal changes started in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Prague. The experienced between-war personnel, among whom about one half (600 persons) returned in function after liberation, stared to be eliminated from the service. Some officials and diplomats were even accused of collaboration with western states and arrested. A part of them was “only” pensioned, but often with minimum pensions. Dr. Havlíček belonged to the second, “luckier” group, being pensioned already on 31 March 1948, only one month after the political regime change. However, in 1952 he became a victim of the s.c. Action B (= Akce byty = action flats), during which politically inconvenient persons were expelled from big cities to make free good flats for the new elite and its partisans. Information about his next destination is scarce. His obituary notice reveals that he died on 11 February 1958, after a lengthy and heavy illness. The fact that just a single person hist obituary notice indicates that he probably passed his last years in isolation. So far, the sad destiny of this notable personality. Remark: Fig. 2-4 (2 x Ships & obituary) are not displayed. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Some of the above mentioned important moments from Havlíček´s diplomatic career are reflected by visa and border control stamps in one of his diplomatic passports (Fig. 5-9). He got it on 15 September 1927, shortly after the introduction of this type of diplomatic passports. Its relatively low number, 391, also reveals this. Similarly, as the then usual passports, it was issued with a validity of only two years, of course with a possibility to be prolonged before the end of its validity or restored after its loss. Before the war, his passport was prolonged four times, with some time overlaps, until 1930, 1935 1939, and, finely, until 15 November 1943 (Fig. 10), always in a Czechoslovak embassy and signed by a lower official. There is, however, missing a note about prolongation for the period from 15 November 1943 until 12 November 1945, when it was prolonged (renewed) at the Czechoslovak embassy in London until 31. December 1945 (Fig. 10 and 11). So it seems that Havlíček used other identity documents for about two years. After return to Czechoslovakia, the passport was prolonged for the last time on 28 December 1945 for five years, until 27 December 1950 (Fig. 10).

On 11 October 1927, Havlíček left by train through Germany to Belgium, where he arrived the next day. Curious is that the Belgian visa is dated 11 September, four days before issuing the passport. During his mission in Belgium, he undertook several travels to England. In 1934 he returned to Czechoslovakia for a short time, but in January 1935, he left through Germany, France, England, and the USA to Japan. From there, he made a journey to France through the USA and a trip to Hawaii.

The next stamp was imprinted into the passports originates as late as 27 august 1942 in Lourenço Marques in Mozambique (Fig. 11), when he boarded the liner Grimpsholm to continue his repatriation travel to England, where he arrives on 9 October 1942 (Fig. 11). After the war, he returned by plane to Czechoslovakia on 25 November 1945, but on 28 December, he left again to England. In late 1947 he definitely returned to Czechoslovakia, as indicated by the stamp confirming receiving rationing cards for food (Fig 12). This is also the last, clearly dated stamp in his passport and, at the same time, the last witness about its use. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Theoretically, Dr. Havlíček could use his passport still almost three years after his pensioning. But it was not easy. Since 23 February 1948, all holders of valid Czechoslovak passports intending to travel abroad needed an allowance (visa) from the National Security Authorities. In summer 1948, this limitation was temporarily withdrawn, but in 1949 a new Passport Act was adopted. In connection with it, all earlier issued and valid Czechoslovak passports of all kinds have become invalid since 30 November 1949. Getting a new one for private purposes was enormously difficult as they could be given just as “exceptions of the new passport act.” This severe practice lasted, as a matter of fact, until 1965, when the new Passport Act partly liberalized this agenda.

The Havlíček´s diplomatic passport is the only Czechoslovak passport known to the author that was almost continuously valid (prolonged, restored) from 1927 to 1950. The usual Czechoslovak passports of persons remaining during the war in the country, which were issued or prolonged not later than in 1937, were (theoretically) valid until 1942. The passports issued in 1938 or early 1939 were mostly issued for a maximum of two years, only rarely for five years, with theoretical validity until 1944. The passports of emigrants in western countries were soon filled by visa and border control stamps. They were to be changed for new passports, mostly for the newly printed ones in England in early 1944 or, rarely, for the pre-war types remaining in stock in some embassies until spring 1945. The passport of Slovak citizens issued was issued in early 1945, with different validity length, sometimes reaching 1947, but they become invalid via fact, with Czechoslovakia’s restoration. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Most Czechoslovak passports used them before the war, usually maximum once a year to a 2-3-week trip to Yugoslavia, often with a short excursion to Venice. But after the war, conditions for private traveling abroad were complicated for both economic and political reasons. They could theoretically ask restoring their pre-war passports, but the possibilities to legally buy foreign money to realize such travels were very limited. The railway tickets could be sold for Czechoslovak crows only to 250 km from the Czechoslovak borders. Due to it, most holders of pre-war passports were neither interested in their restoration. The new passports were issued after the war just for concrete travel and for several months only. The longer private travels were made only rarely. Due to its chance to find other passports with similar length of validity like the Havlíček´s passport is very low. Czechoslovak diplomatic passport

Although Havlíček´s passport does not completely reflect all episodes from his diplomatic career, especially the most adventurous ones from World War II, it fairly shows how this type of document can illustrate how individual persons passed not only the dramatic events of their life but also the crucial epochs of the world´s history.

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...