8 Billion People On Earth – 12 On The Moon And 1 Passport

Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

John Young was NASA’s longest-serving astronaut. He first became an astronaut when the agency was flying two-man space capsules. He left when the agency was flying the space shuttle. In between, he flew six space missions — the first person to do so. In his decades with the agency, Young racked up several milestones. He made it to the moon’s neighborhood twice and walked on it once. He commanded the first space shuttle flight and then came back into space yet again to command another. His flight experience spanned three different programs: Gemini, Apollo, and the space shuttle. In 2004, with an impressive 15,000 hours of spaceflight training across four decades, Young retired from the agency. Young died on Jan. 5, 2018, following complications from pneumonia. He was 87.

Selected alongside Neil Armstrong and Jim Lovell with NASA’s second group of astronauts in 1962, Young flew two Gemini missions, two Apollo missions, and two space shuttle missions. He was one of only three astronauts to launch to the moon twice and was the ninth person to step foot on the lunar surface. In total, Young logged 34 days, 19 hours, and 39 minutes flying in space, including 20 hours and 14 minutes walking on the moon. “I’ve been very lucky, I think,” Young said in a NASA interview in 2004 when he retired from the space agency after 42 years.

John Watts Young was born on Sept. 24, 1930, in San Francisco, Calif. When he was 18 months old, Young’s parents moved, first to Georgia and then Orlando, Florida, where he attended elementary and high school. Young earned his bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering from the Georgia Institute of Technology in 1952. After graduation, he entered the U.S. Navy, serving on the destroyer USS Laws in the Korean War and then entering flight training before being assigned to a fighter squadron for four years.

Young graduated from the U.S. Navy Test Pilot School in 1959 and served at the Naval Air Test Center at Naval Air Station Patuxent River in Maryland, where he evaluated Crusader and Phantom fighter weapons systems. In 1962, he set world time-to-climb records to 3,000 and 25,000-meter (82,021 and 9,843-feet) altitudes in the F-4 Phantom.

NASA picked Young as an astronaut in September 1962, just as the one-man Mercury spacecraft program was winding down and the Gemini program was starting up. Young flew on the first manned Gemini flight — Gemini 3 — in 1965, transferring his test pilot skills to figuring out the new spacecraft. Young then joined Michael Collins to do two rendezvous with two separate target Agena spacecraft in 1966, during Gemini 10. Working in close vicinity with other spacecraft was a requirement for moon missions when two spacecraft would need to dock together to get to the moon and return home. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

This experience came in handy for Apollo 10 in 1969, which featured the first moon-orbiting docking between two spacecraft. At the controls of the command module Charlie Brown, Young successfully joined with the lunar module, Snoopy, that had been doing a landing test a few miles above the surface. “Snoopy and Charlie Brown are hugging each other!” said an exuberant Tom Stafford, who was commanding Apollo 10.

Young went back to the moon in 1972, during Apollo 16. He commanded a scientifically ambitious journey to the Descartes highlands, searching for volcanic rock and some possible clues to the moon’s history. He and his crewmates, Charles Duke and Ken Mattingly, brought back 200 lbs. of rock for more than 20 hours on the surface. Young and Duke only found sedimentary rocks along the way, which surprised scientists back home. Despite the challenges, however, the men kept their sense of humor. They did a controlled but wild-looking test with the lunar rover, for example, skidding it across the surface in front of a video camera.

“One-sixth gravity on the surface of the moon is just delightful,” Young said in a 2006 interview with NASA. “It’s not like being in zero gravity, you know. You can drop a pencil in zero gravity and look for it for three days. In one-sixth gravity, you just look down and there it is.”

In 1974, Young was named the fifth chief of the Astronaut Office, after serving for a year as the office’s space shuttle branch chief. For 13 years, Young led NASA’s astronaut corps, overseeing the crews assigned to the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the approach and landing tests with the prototype orbiter Enterprise, and the first 25 space shuttle missions. In 1981, Young moved to a very different kind of vehicle: the space shuttle, which acted and performed more like a plane than a spacecraft. Development on the ambitious vehicle was not without its challenges, as Young and his crewmate Robert Crippen discovered. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

“I remember [senior NASA official Bob] Gilruth telling me it’s going to be as reliable as a DC-8 and right after he said that, Crip and I, every time we went out to Rocketdyne or somewhere to see what was happening, engines were blowing up. So I wasn’t sure it was going to be as reliable as a DC-8. It was a lot of fun,” Young quipped. Young and Crippen lifted off in the space shuttle Columbia (STS-1) in April 1981, on a test flight of a vehicle that had never before been used in space. There were questions about how its systems would perform, and whether the new tile heat-shield system for re-entry would hold up. The flight was a success.

Still with a taste for spaceflight, Young returned to space once more at the helm of STS-9. This flight, like his last Apollo mission, was scientifically heavy. The crew flew the experimental Spacelab module for the first time, performing hours of experiments for ten days. “The mission returned more scientific and technical data than all the previous Apollo and Skylab missions put together,” NASA stated.

After the loss of space shuttle Challenger and its seven-person crew in January 1986, Young penned internal memos critical of NASA’s attention to safety, a topic he had championed since his days flying Gemini. Young expressed concern over schedule pressure and wrote that other astronauts who had launched on missions preceding the ill-fated STS-51L mission were “very lucky” to be alive.

Young was subsequently reassigned to be a special assistant to the director of the Johnson Space Center for engineering, operations, and safety until 1996, when he was named the associate director for technical affairs, a position he held until his retirement from NASA on Dec. 31, 2004. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

“I don’t think it changed it any,” he told the Houston Chronicle in 2004. “You just had to learn a lot of systems and learn how to operate them and be a systems person. That’s what we were. We were systems operators.”

The Passport

THERE ARE 7 BILLION PEOPLE ON EARTH AND ONLY 12 PEOPLE HAVE BEEN ON THE MOON!

THIS PASSPORT IS A MOST IMPORTANT DOCUMENT IN THE HISTORY OF MANKIND!

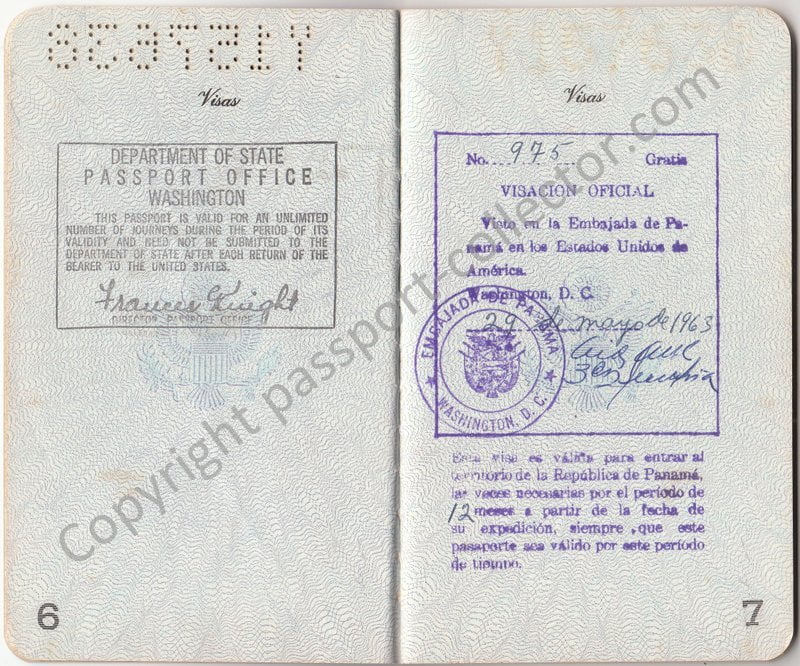

Official United States Passport in the name of JOHN WATTS YOUNG, issued on April 23, 1963, with full signature. Passport No. Y156738. The travel document has the remark “ABROAD ON AN OFFICIAL ASSIGNMENT FOR THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT.” Page seven shows a visa from PANAMA, issued at their in Washington D.C. (Jungle survival training was conducted at the USAF Tropic Survival School at Albrook Air Force Station in PANAMA, desert survival training at Stead Air Force Base in Nevada, and water survival training on the Dilbert Dunker at the USN school at the Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida and on Galveston Bay.). Page nine a visa of Guatemala, also issued in Washington D.C. Finally, there is a passport renewal on page eight from 1966 until 1968. All the other pages of the 48-page passport are empty. The condition of the document is excellent.

Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

For many years I tried to get a MOONWALKER into my collection. Finally, I succeeded. THANK YOU, MICHAEL! Please read further as only then someone understands what it really meant to be an ASTRONAUT in the early days of SPACE AGE. JOHN YOUNG was one of its finest! Young, commanded also the first Space Shuttle mission, STS-1, Columbia.

NEIL ALDEN ARMSTRONG – EDWIN “BUZZ” ALDRIN – CHARLES “PETE” CONRAD – ALAN L. BEAN – ALAN SHEPARD – EDGAR D. MITCHELL – DAVID RANDOLPH SCOTT – JAMES B. IRWIN – JOHN WATTS YOUNG – CHARLES M. DUKE JR. – HARRISON “JACK” SCHMITT – EUGENE E. CERNAN (Only four of these great men are still alive today).

NASA’s Astronaut Group 2, also known as the New Nine and the Next Nine, was the second group of astronauts selected by NASA. Their selection was announced on September 17, 1962. The nine astronauts were Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Pete Conrad, Jim Lovell, James McDivitt, Elliot See, Tom Stafford, Ed White, and John Young. Six of the nine flew to the Moon (Lovell and Young twice), and Armstrong, Conrad, and Young walked on it as well. Seven of the Nine were awarded the Congressional Space Medal of Honor.

The group was required to augment the original Mercury Seven, with the announcement of the Gemini program leading to the Apollo program. While the Original seven had been selected to accomplish the more straightforward task of orbital flight, the new challenges of rendezvous and lunar landing led to the selection of candidates with advanced engineering degrees (for four of the nine) as well as test pilot experience. Lovell and Conrad had been candidates for the original seven but were not selected then. The nine became the first group with civilian test pilots; See had flown for General Electric, while Armstrong had flown the X-15 research plane for NASA. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

Background

The launch of the Sputnik 1 satellite by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957, started a Cold War technological and ideological competition with the United States known as the Space Race. The demonstration of American technological inferiority came as a profound shock to the American public. In response to the Sputnik crisis, the President of the United States, Dwight D. Eisenhower, created a new civilian agency, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), to oversee an American space program. The Space Task Group (STG) at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia created an American manned spaceflight project called Project Mercury. The selection of the first astronauts, known as the “Original Seven” or “Mercury Seven,” was announced on April 9, 1959.

By 1961, although it was yet to launch a man into space, the STG was confident that Project Mercury had overcome its initial setbacks, and the United States had overtaken the Soviet Union as the most advanced nation in space technology. The STG began considering Mercury Mark II, a two-man successor to the original Mercury spacecraft. This confidence was shattered on April 12, 1961, when the Soviet Union launched Vostok 1, and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first man to orbit the Earth. In response, President John F. Kennedy announced a far more ambitious goal on May 25, 1961: to put a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. The effort to land a man on the Moon already had a name: Project Apollo. The two-man Mercury II spacecraft concept did not die; the STG head Robert R. Gilruth formally announced it on December 7, 1961, and on January 3, 1962, it was officially named Project Gemini. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

On April 18, 1962, NASA formally announced that it was accepting applications for a new group of astronauts who would assist the Mercury astronauts with Project Mercury, and join them in flying Project Gemini missions. It was anticipated that they might go on to command Project Apollo missions. Unlike the selection process for the Mercury Seven, which was carried out in secret, this selection was widely advertised, with public announcements and the minimum standards communicated to the aircraft companies, government agencies and the Society of Experimental Test Pilots.

Selection criteria

The five minimum selection criteria were that applicants:

- were experienced test pilots, with 1,500 hours test pilot flying time, who had graduated from a military test pilot school, or had test pilot experience with NASA or the aircraft industry;

- had flown high-performance jet aircraft;

- had earned a degree in engineering or the physical or biological sciences;

- Were a U.S. citizen, under 35 years of age, and 6 feet 0 inches (1.83 m) or less; and

- recommended by the employer.

The criteria differed from those of the Mercury Seven selection in several ways. The Gemini spacecraft was expected to be more capacious than the Mercury one, so the height requirement was relaxed slightly. This made Tom Stafford eligible. A college degree was now absolutely required but could be in the biological sciences. Civilian test pilots were now eligible, but the requirement for experience in non-performance jets favored those with recent experience and fighter pilots over those with multi-engine experience. Perhaps the most important change was lowering the age limit from 40 to 35. This was because whereas Mercury was a short-term project, Project Apollo was going to run until the end of the decade at least. The changed selection criteria meant that the selection panel could not merely select another group from the Mercury Seven finalists. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

At this time Jerrie Cobb was pressing for women to be allowed to become astronauts, and Mercury 13 had passed the same medical tests given to the Mercury Seven astronauts. Although women were not prevented from applying, the requirement for jet test pilot experience effectively excluded them. NASA Administrator James E. Webb told the media that “I do not think we shall be anxious to put women or any other person of particular race or creed into orbit just for the purpose or putting them there.”

Selection process

The U.S. Navy (USN) and U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) submitted the names of all their pilots who met the selection criteria, but the U.S. Air Force(USAF) conducted its internal selection process, and only submitted the names of eleven candidates. The Air Force ran them through a brief training course in May 1962 on how to speak and conduct themselves during the NASA selection process. The candidates called it a “charm school.” The Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General Curtis LeMay, who told them: “There are a lot of people who’ll say you’re deserting the Air Force if you’re accepted into NASA. Well, I’m the Chief of the Air Force, and I want you to know I want you in this program. I want you to succeed in it, and that’s your Air Force mission. I can’t think of anything more important”. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

In all, 253 applications were received by the June 1, 1962 deadline. Neil Armstrong submitted his application a week after the deadline, but Walter C. Williams, the associate director of the Space Task Group, wanted the NASA test pilot, so he had Richard Day, who acted as secretary of the selection panel, add it to the pile of applications when it arrived. Paul Bikle, the director of the NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Facility, declined to recommend Armstrong for astronaut selection because he had misgivings about Armstrong’s performance.

The three-man selection panel consisted of Mercury Seven astronauts Alan Shepard and Deke Slayton, and NASA test pilot Warren J. North, although Williams sat in on some sessions. They reduced the candidates to a more manageable 32 finalists, from whom they hoped to select between five and ten new astronauts. The Air Force’s pre-selection process seems to have been successful; nine of the eleven were chosen as finalists, and one of those rejected, Joe Engle, was selected in a later intake in 1966. Of the rest, thirteen were from the Navy, four were Marines, and six were civilians. Four had been finalists in the Mercury Seven selection: Pete Conrad, Jim Lovell, John Mitchell, and Robert Solliday. Lovell was not selected due to a high bilirubin blood count.

The finalists were sent to Brooks Air Force Base in San Antonio for medical examinations. The tests there were much the same as those employed to select the Mercury Seven. One candidate, Lieutenant Commander Carl (Tex) Birdwell, was found to be 2 inches (51 mm) too tall.[24] Another four were eliminated based on ear, nose, and throat examinations. The remaining 27 then went to Ellington Air Force Base near Houston, where the Manned Spacecraft Center (MSC) was being established. The selection panel individually interviewed them. Nine candidates were selected, and their names forwarded to Gilruth for approval. Slayton informed each of them by phone on September 14, before a public announcement was made on September 17. The media crowded into the 1.800-seat Cullen auditorium at the University of Houston for the announcement, but it was a more low-key event than the unveiling of the Mercury Seven three years before. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

As with those who had been passed over in the Mercury Seven selection, most of the rejected finalists went on to have distinguished careers. William E. Ramsey became a vice admiral in the Navy, and Kenneth Weir, a major general in the Marine Corps. Four would later be selected as NASA astronauts: Alan Bean, Michael Collins and Richard Gordon in 1963, and Jack Swigert in 1966.

Demographics

The nine astronauts were Neil Armstrong, Frank Borman, Pete Conrad, Jim Lovell, James McDivitt, Elliot See, Tom Stafford, Ed White, and John Young. Conrad, Lovell, and Young were from the Navy; Borman, McDivitt, Stafford, and White from the Air Force; and Armstrong and See were civilians. All were male and white, married with an average of two children. Their average age was 32.5, two years younger than the Mercury Seven at the time of selection. They had an average of 2,800 flying hours each, 1,900 of them in jets. This was 700 fewer flying hours than the Mercury Seven, but 200 more hours in jets. Their average weight was slightly higher — 161.5 pounds (73.3 kg) compared to 159 pounds (72 kg). All had a college education. Three had master’s degrees: Borman had a Master of Science degree in aeronautical engineering from the California Institute of Technology, See had one from the University of California at Los Angeles, and White had one from the University of Michigan. Armstrong, Conrad, McDivitt, and Young all had engineering degrees, and Lovell and Stafford had science degrees from the United States Naval Academy. Their mean IQ was 132.1 on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. Borman and McDivitt were early graduates of the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School (ARPS).

Training

The new astronauts became known as the Next Nine or the New Nine. They moved to the Houston area in October 1962. Most bought lots and built houses in Nassau Bay, a new development to the east of the MSC. Conrad and Lovell built homes in Timber Cove, south of the MSC. Developers in Timber Cove and Nassau Bay offered mortgages with small down payments and low-interest rates. The MSC complex was not yet complete, so NASA temporarily leased office space in Houston. Slayton’s wife Marge and Borman’s wife Susan organized an Astronauts’ Wives Club, along the lines of the Officers’ Wives Clubs that were a feature of military bases. As Slayton was in charge of astronaut activities, Marge was considered to be the equivalent of the commanding officer’s wife. The Nine were honored guests at Houston society parties, such as those thrown by socialite Joanne Herring, and their wives received $1,000 Neiman Marcus gift vouchers (equivalent to $8,000 in 2018) from an anonymous source. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

A lawyer, Henry Batten, agreed to negotiate a deal for their personal stories with Field Enterprises along the lines of the Life magazine deal enjoyed by the Mercury Seven, for no fee. As with the Life deal, there was some disquiet about the propriety of astronauts cashing in on government-created fame, but Mercury Seven astronaut John Glenn intervened, and personally raised the matter with Kennedy, who approved the deal. The deals with Field and Time-Life earned each of the Nine $16,250 (equivalent to $135,000 in 2018) per annum over the next four years and provided them with $100,000 life insurance policies (equal to $828,000 in 2018). Due to the dangerous nature of an astronaut’s job, insurance companies would have charged them unaffordably high premiums.

As Slayton was busy with Project Gemini, he delegated the task of supervising the Nine’s training to Mercury Seven astronaut Gus Grissom. Initially, each of the astronauts was given four months’ of classroom instruction on subjects such as spacecraft propulsion, orbital mechanics, astronomy, computing, and space medicine. Classes were for six hours a day, two days a week, and all sixteen astronauts had to attend. There was also familiarization with the Gemini spacecraft and Titan II and Atlas boosters, and the Agena target vehicle. Jungle survival training was conducted at the USAF Tropic Survival School at Albrook Air Force Station in Panama, desert survival training at Stead Air Force Base in Nevada, and water survival training on the Dilbert Dunker at the USN school at the Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida and on Galveston Bay. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

Following the precedent set by the Mercury Seven, each of the Nine was assigned a particular area in which to develop expertise that could be shared with the others and to provide astronaut input to designers and engineers. Armstrong was responsible for trainers and simulators; Borman for boosters; Conrad for cockpit layout and systems integration; Lovell for recovery systems; McDivitt for guidance systems; See for electrical systems and mission planning; Stafford for communications systems; White for flight control systems; and Young for environmental control systems and space suits.

Legacy

Collins wrote that in his opinion “this group of nine was the best NASA ever picked, better than the seven that preceded it, or the fourteen, five, nineteen, eleven and seven that followed.” Slayton felt so too, describing them as “probably the best all-around group ever put together.” The Nine were deficient in only one respect: there were also few of them. Looking over the tentative schedule of Apollo missions, Slayton calculated that up to 14 three-man crews might be required, but the 16 astronauts on hand could fill just five. While he considered the schedule to be optimistic, he did not want a shortage of astronauts to be the reason the schedule could not be met and therefore proposed that there be another round of recruiting. On June 5, 1963, NASA announced that it was seeking another ten to fifteen new astronauts. Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

The Nine went to illustrious careers as astronauts. Apart from See and White, who were killed a T-38 crash and the Apollo fire, all went on to command Gemini and Apollo missions. Six of the nine flew to the Moon (Lovell and Young twice), and Armstrong, Conrad, and Young walked on it as well. Seven of the nine received the Congressional Space Medal of Honor for their service, valor, and sacrifice:

- White, posthumously, killed in the Apollo 1 fire;

- Borman, for commanding Apollo 8, the first manned mission to the Moon;

- Armstrong, for commanding Apollo 11, the first lunar landing;

- Lovell, for commanding the ill-fated Apollo 13;

- Conrad, for commanding Skylab 2, and saving the damaged station;

- Stafford, for commanding the international Cold War Apollo-Soyuz Test Project; and

- Young, for commanding the first Space Shuttle mission, STS-1, Columbia.

Seven Billion People On Earth – Twelve On The Moon And One Passport

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...