Japanese-American in U.S. Concentration Camps

Japanese-American Concentration Camp

Miyeko Takita (1924- ), a Japanese-American woman, was sent with her mother, Aoyagi Takita, and sister, Aiko Takita (1926- ), to the Tanforan Assembly Center, a temporary detention camp in San Bruno, California, in the spring of 1942, and the Topaz War Relocation Center in Millard County, Utah, on 1942 October. The Takita sisters were released from the Topaz internment camp, where they were involved in school, music, and the Protestant church in 1945 October. In 1949, Miyeko Takita was a United States government employee working as a special services librarian in Munich, Germany. This is her passport issued in 1949 at the U.S. Consulate General in Munich, Germany. Her passport is most valuable in several aspects.

- Japanese-Americans were detained to two concentration camps in the USA

(A history which is still not much known in the USA and not much taught in schools) - Early post-war passport issue at Munich U.S. Consulate

- Allied Military Visa with GRATIS-Revenue stamp

- Early German border stamps from Allied controlled zones to Federal Germany

Ms. Takita worked at the Special Services Library Depot Nuremberg Military Post. Sam E. Woods was Consul General in Munich since 1947 and signed the passport. Over 30+ years, Woods held several diplomatic positions, including assistant trade commissioner in Czechoslovakia; commercial attache in Prague; commercial attache at large in Berlin; consul general in Switzerland, and consul general with the personal rank of minister in Germany. Woods became immersed in the diplomatic society in these roles, making many contacts.

Japanese-American Concentration Camps

When one thinks of concentration camps, what usually comes to mind are the Nazi Germany camps of World War II. Still, many may not realize that the United States had its version of concentration camps during that era. While nearly nothing like the Nazi camps and lacking such an evil purpose, a United States version of concentration camps – some top government brass (including President Franklin D. Roosevelt himself) even called them that – did exist. Their aim, however, wasn’t to eliminate people; their objective was to keep a watchful eye on an entire race – those of Japanese ancestry – approximately two-thirds of whom were American citizens. They were known more formally as internment camps or the more euphemistic “relocation centers.” Japanese-American Concentration Camp

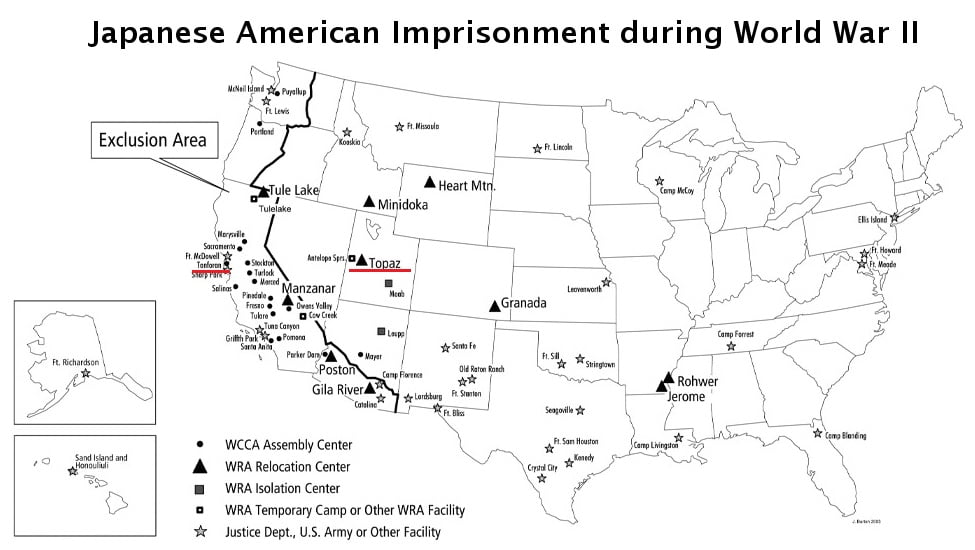

During World War II, the internment of Japanese Americans in the United States was the forced relocation and incarceration in concentration camps in the western interior of the country of about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most of whom lived on the Pacific Coast. Sixty-two percent of the internees were United States citizens. President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered these actions shortly after Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

Roosevelt authorized Executive Order 9066, issued on February 19, 1942, which allowed regional military commanders to designate “military areas” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” Although the executive order did not mention Japanese Americans, this authority was used to declare that all Japanese ancestry were required to leave Alaska and the military exclusion zones from all of California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, except for those in government camps. Approximately 5,000 Japanese Americans relocated outside the exclusion zone before March 1942, while some 5,500 community leaders had been arrested immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack and thus were already in custody.

Miyeko was first in the Tanforan Assembly Center and then the Topaz War Relocation Center. Japanese-American Concentration Camp

Tanforan Assembly Center

The Tanforan Assembly Center was opened on April 28, 1942. Until October 1942, housed 8,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry, most of the citizens, evicted from their homes and imprisoned during World War II in the San Francisco Bay Area. Tanforan served as a temporary detention center for Japanese Americans until they were shipped to more permanent concentration camps, the majority being sent to Topaz in Utah. This was done without filed charges and due process guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution.

Topaz War Relocation Center

The Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) Site, also referred to as the Topaz Relocation Center or Topaz, was located in west-central Utah, just north of the town of Delta and 140 miles southwest of Salt Lake City. Topaz was one of 10 relocation centers constructed in the United States during World War II to detain Japanese Americans and people of Japanese descent. More than 11,000 people passed through the center, and, at its peak, it housed over 8,000 internees. Today, the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) Site consists of two monuments, building foundations, roads, gravel walkways, agricultural buildings, portions of the perimeter fence, and landscaping. They called Topaz after a nearby mountain. Japanese-American Concentration Camp

The Central Utah Relocation Center officially opened on September 11, 1942. The camp had a one square mile central area consisting of 42 blocks with 12 barracks each, housing 250 to 300 internees. Each block also had a recreation room, a combination washroom-toilet-laundry building, a central dining hall, and an office for the block manager. The barracks were constructed of pine planks covered with tarpaper with sheetrock on the inside walls for insulation. Each barrack unit was furnished with pot-bellied stoves, army cots, blankets, and mattress covers. The barracks were barely ready when the evacuees moved into the center, and many of them helped finish the construction and built their furniture. Thousands of trees and shrubs were planted throughout the developed area of the camp, and internees engaged in extensive landscaping of the barracks areas. The relocation center eventually consisted of 623 buildings, including two elementary schools, one junior/senior high school, a hospital, a church, seven watchtowers, a perimeter fence, and a sentry post.

Topaz was considered a “quieter” center of the ten relocation centers. The most significant unrest, including organized protests, happened in April 1943 due to a military guard’s shooting death of 63-year-old internee James Hatsuki Wakasa. Wakasa was walking near the perimeter fence and was either distracted or unable to hear or understand the guard’s warnings. After this and another incident a month later, when a guard fired at a couple strolling too close to the fence, security regulations at Topaz were reevaluated. The center administration restricted the military’s use of weapons, and access to Topaz and security was relaxed. Internees were able to get permission to leave the camp for recreational activities and jobs in the nearby town of Delta. Japanese-American Concentration Camp

By the way, in WWI, civil and resident German-Americans were also in Concentration Camps! Same in WWII but then also Italian-Americans!

The Passport

A fantastic document about a time in U.S. history, which is less known but getting more dynamic nowadays by advocates like George Takei.

According to this article, American schools as a whole may not have overtly downplayed the Japanese American internment. Still, the mere fact that it is glossed over, reduced to a sidebar on a page of a history book (nearly a third of the responders used the word “sidebar” to describe how they learned about the camps) tacitly teaches Americans that it “wasn’t that bad.” Japanese-American in U.S. Concentration Camp

FAQ Passport History

Passport collection, passport renewal, old passports for sale, vintage passport, emergency passport renewal, same day passport, passport application, pasaporte passeport паспорт 护照 パスポート جواز سفر पासपोर्ट

1. What are the earliest known examples of passports, and how have they evolved?

The word "passport" came up only in the mid 15th Century. Before that, such documents were safe conducts, recommendations or protection letters. On a practical aspect, the earliest passport I have seen was from the mid 16th Century. Read more...

2. Are there any notable historical figures or personalities whose passports are highly sought after by collectors?

Every collector is doing well to define his collection focus, and yes, there are collectors looking for Celebrity passports and travel documents of historical figures like Winston Churchill, Brothers Grimm, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Read more...

3. How did passport designs and security features change throughout different periods in history, and what impact did these changes have on forgery prevention?

"Passports" before the 18th Century had a pure functional character. Security features were, in the best case, a watermark and a wax seal. Forgery, back then, was not an issue like it is nowadays. Only from the 1980s on, security features became a thing. A state-of-the-art passport nowadays has dozens of security features - visible and invisible. Some are known only by the security document printer itself. Read more...

4. What are some of the rarest and most valuable historical passports that have ever been sold or auctioned?

Lou Gehrig, Victor Tsoi, Marilyn Monroe, James Joyce, and Albert Einstein when it comes to the most expensive ones. Read more...

5. How do diplomatic passports differ from regular passports, and what makes them significant to collectors?

Such documents were often held by officials in high ranks, like ambassadors, consuls or special envoys. Furthermore, these travel documents are often frequently traveled. Hence, they hold a tapestry of stamps or visas. Partly from unusual places.

6. Can you provide insights into the stories behind specific historical passports that offer unique insights into past travel and migration trends?

A passport tells the story of its bearer and these stories can be everything - surprising, sad, vivid. Isabella Bird and her travels (1831-1904) or Mary Kingsley, a fearless Lady explorer.

7. What role did passports play during significant historical events, such as wartime travel restrictions or international treaties?

During war, a passport could have been a matter of life or death. Especially, when we are looking into WWII and the Holocaust. And yes, during that time, passports and similar documents were often forged to escape and save lives. Example...

8. How has the emergence of digital passports and biometric identification impacted the world of passport collecting?

Current modern passports having now often a sparkling, flashy design. This has mainly two reasons. 1. Improved security and 2. Displaying a countries' heritage, icons, and important figures or achievements. I can fully understand that those modern documents are wanted, especially by younger collectors.

9. Are there any specialized collections of passports, such as those from a specific country, era, or distinguished individuals?

Yes, the University of Western Sidney Library has e.g. a passport collection of the former prime minister Hon Edward Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret. They are all diplomatic passports and I had the pleasure to apprise them. I hold e.g. a collection of almost all types of the German Empire passports (only 2 types are still missing). Also, my East German passport collection is quite extensive with pretty rare passport types.

10. Where can passport collectors find reliable resources and reputable sellers to expand their collection and learn more about passport history?

A good start is eBay, Delcampe, flea markets, garage or estate sales. The more significant travel documents you probably find at the classic auction houses. Sometimes I also offer documents from my archive/collection. See offers... As you are already here, you surely found a great source on the topic 😉

Other great sources are: Scottish Passports, The Nansen passport, The secret lives of diplomatic couriers

11. Is vintage passport collecting legal? What are the regulations and considerations collectors should know when acquiring historical passports?

First, it's important to stress that each country has its own laws when it comes to passports. Collecting old vintage passports for historical or educational reasons is safe and legal, or at least tolerated. More details on the legal aspects are here...

Does this article spark your curiosity about passport collecting and the history of passports? With this valuable information, you have a good basis to start your own passport collection.

Question? Contact me...